Tag: security

-

Building scalable monitoring infrastructure from scratch

In this talk we will share our experience of creating a transaction monitoring solution for the EVM-compatible networks. Starting from a standalone Rust application that queries the blockchain RPCs, and ending with a scalable solution that can handle thousands of transactions per second, we will cover all the steps that will explain how to catch…

-

Upgradeable smart contracts security

Slides & video from my talk about the security of proxies in smart contracts at OFFZONE 2022

-

Сушите вёсла #20

Принял участие в новом эпизоде подкаста “Сушите вёсла”, посвященном блокчейну, смарт-контрактам и их безопасности. Приятного прослушивания!

-

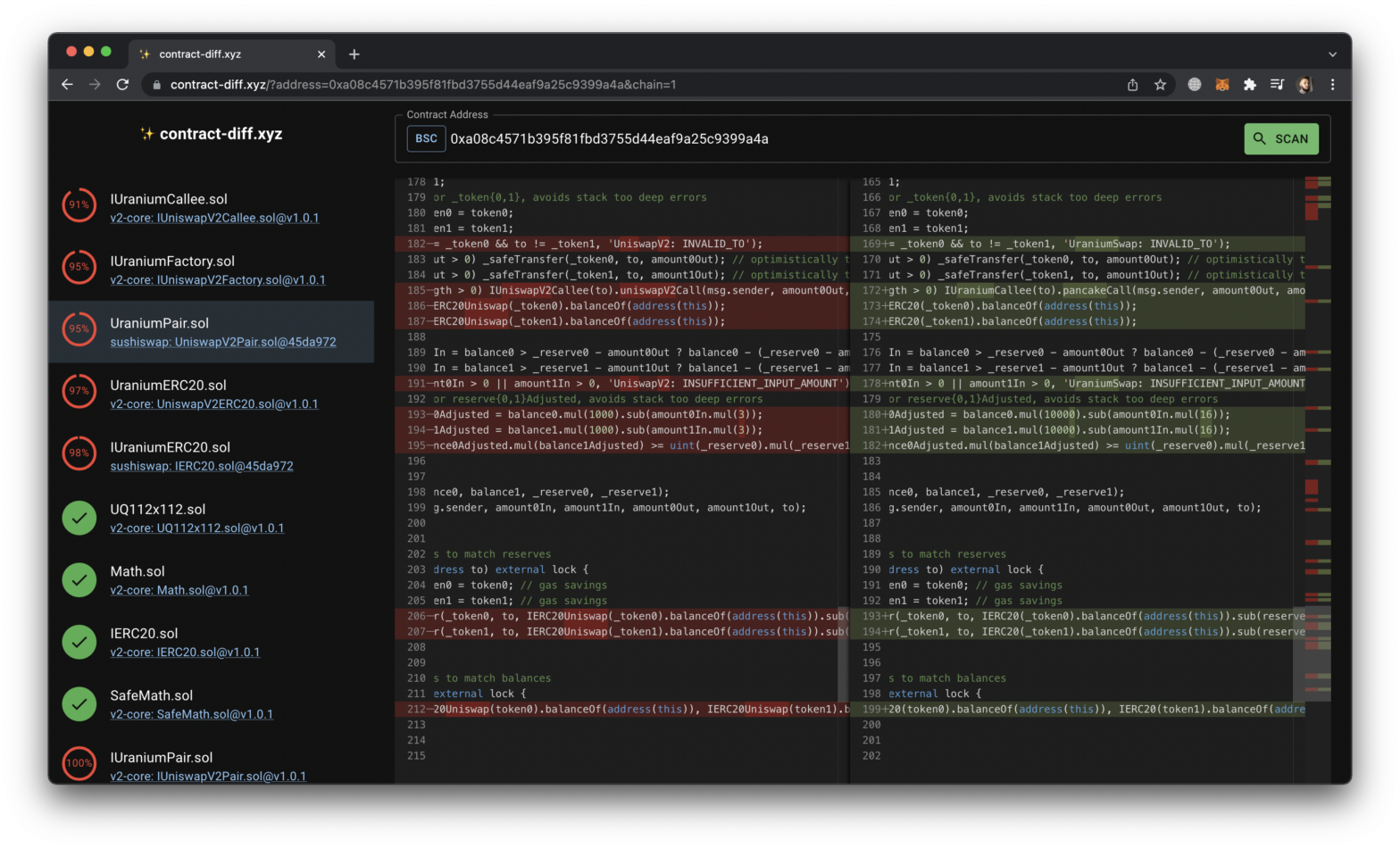

contract-diff: find bugs in smart contract forks

There has been plenty of hacks when a smart contract was forked and some things were changed without full understanding of the code. To help auditors I have built https://contract-diff.xyz This is how it works 🧵 For popular contracts like OpenZeppelin, Uniswap, Sushiswap, etc two kinds of hashes were computed: md5 hashsums & simhashes. Using…

-

Безопасность web3: уязвимости на стыке блокчейна и веб-технологий

-

Using CodeQL to detect client-side vulnerabilities in web applications

GitHub’s CodeQL is a robust query language originally developed by Semmle that allows you to look for vulnerabilities in the source code. CodeQL is known as a tool to inspect open source repositories, however its usage is not limited just to it. In this article I will delve into approaches on how to use CodeQL…

-

DeFi Hack solutions: DiscoLP

This is a series of write-ups on DeFi Hack, a wargame based on real-world DeFi vulnerabilities. Other posts: DiscoLP DiscoLP is a brand new liquidity mining protocol! You can participate by depositing some JIMBO or JAMBO tokens. All liquidity will be supplied to JIMBO-JAMBO Uniswap pair. By providing liquidity with us you will get DISCO…

-

DeFi Hack solutions: May The Force Be With You

Back in 2018 I hosted the contest EtherHack which featured a set of vulnerable smart contracts. At that time the tasks were focused primarily on the EVM peculiarities like insecure randomness or extcodesize opcode tricks. Back then the first wave of crypto hype was coming to the end when numerous ICOs were falling apart because…

-

Why you should not use GraphQL schema generators

It has been quite a while since GraphQL has been introduced by Facebook, lots of tools and frameworks has appeared and are being used in the wild now. In 2017 I made an overview of the technology from the security point of view in the post “Looting GraphQL for Fun and Profit” and some of…

-

PolySwarm Smart Contract Hacking Challenge Writeup

This is a walk through for the smart contract hacking challenge organized by PolySwarm for CODE BLUE conference held in Japan on November 01–02. Although the challenge was supposed to be held on-site for whitelisted addresses only, Ben Schmidt of PolySwarm kindly shared a wallet so that I could participate in the challenge.